- Rough is made possible by

Keetra Dean Dixon is a Designer, Director, Artist and Teacher. Her hybrid design background and expertise in graphic design often leads her work towards speculative terrain, leveraging emergent technologies and the shortcomings of ubiquitous creative tools. She has been recognized on several fronts including a U.S. presidential award, a place in the permanent design collection at the SFMOMA, and the honorable ranking of ADC Young Gun (6). She has been featured in numerous publications and exhibits, including feature articles in Time, étapes, + Surface, commissioned works for the ’09 U.S. Presidential Inauguration and the ’12 Olympic games.

I grew up in Alaska, in a relatively populated area of Alaska, right outside of Anchorage. My parents were makers. My dad was a metal-smith and my mom worked as a seamstress. I grew up in a very hands on, practical fabrication kind of household. Everybody has a pretty natural inclination to the visual world, and I ended up doing painting and drawing. I went into undergrad for painting on a scholarship where I was seduced into graphic design via gestalt psychology. I liked having a bit of a rule-set that was based on perception. I found that really rewarding. That's kind of why I identify a little bit more with the design title than the art title, but now with the self-authored work that I do, I kind of drifted back into this broader field of visual practice.

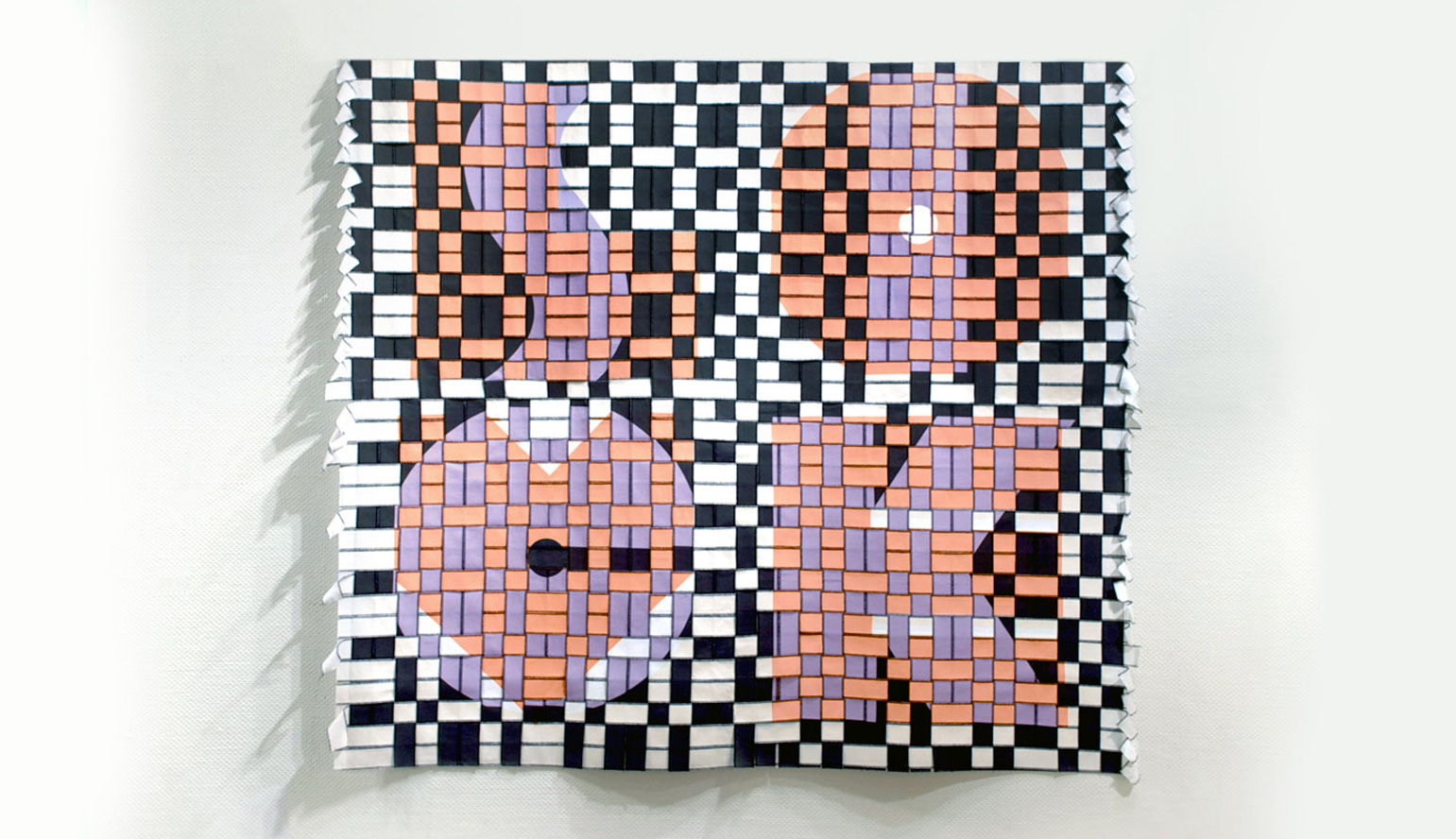

I think a majority of my public facing work falls into three different buckets. There's the experiential design, which is a relatively recognizable title. I think you can explain that practice as interaction in physical spaces. It's a little bit between event design, theater design, interior design, graphic design, etc... It's a convergence of all of those things.

Secondly, I've kind of been dabbling. I say that because it's very amateur. It's novice production but with object design. Those are short-run fabricated pieces.

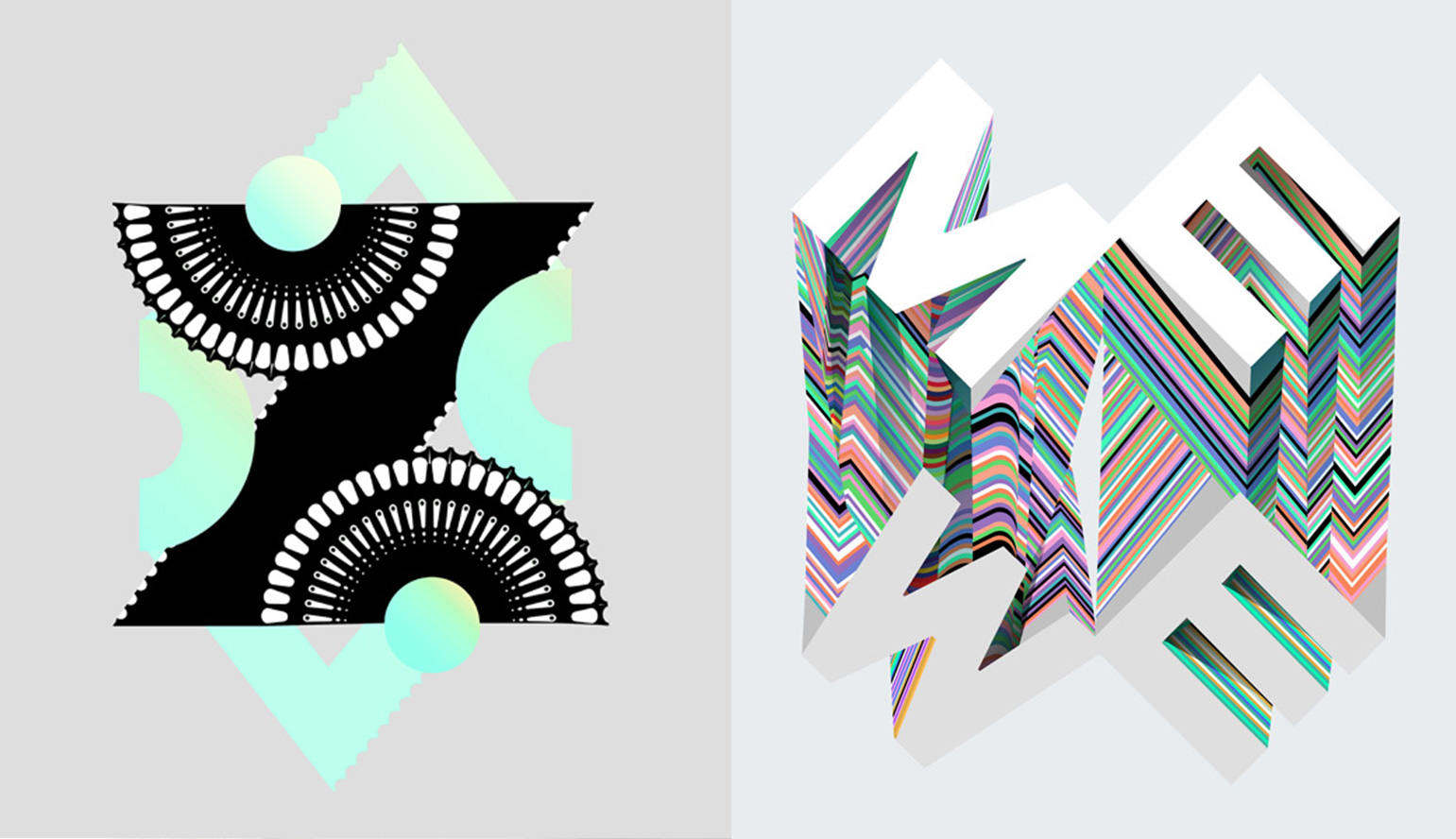

The third category would be work with lettering or language. That is probably closest rooted to my traditional 2-D graphic design background. Often times I am asked to do spot illustration. For that I do the lettering or working with language. I'll then also I do some kind of a bigger jump away from 2-D graphic design. I do dimensional exploration through language and sculptural form, but that also fits into the lettering category

Yes! All of them utilize that design thinking. It's the final medium that is to be determined by the context that I'm working in.

I think actually you hit on the two most influential professional exposures. Both of those working contexts and why they impacted me so much were because they were with this major shift or growth or in the case of the 90s, the .com boom, this change of how technology was existing in mainstream media.

At Future Farmers, before I started working with them ... For undergrad I actually went to school at a place that, I might be lying when I say this I haven't fact checked myself, supposedly they had the first major for interaction design in the United States, where you could actually define that as how you were going to graduate with your degree in interaction. The guy that I was dating at the time graduated as one of the first to be an interactive designer. There were a group of nine people that graduated with that and those were my main peers in undergrad. I was graphic design major, but I had a lot of influence as far as what was going on with the internet through those peers.

We moved out to San Francisco and I was familiar with Future Farmers work only in passing, only in a ... I was very enamored by their aesthetic. I thought they were adorable, fantastical, really charming, and charismatic as far as their look and feel was concerned. I hadn't spent a lot of time investigating what their position was in the emerging media realm, in this what is the internet going to be, or interacting with their projects. I didn't understand how much they were helping what interaction was becoming as for as the web.

Somehow, I stumbled into an opportunity to work with them and at the time it was Amy Franceschini who really could be noted as the founder of future farmers. She would bring on different people depending on what work she was doing and for a moment she brought me in and it all went from there. It was really just a fortunate circumstance that I stumbled in. I somehow managed to be a helpful hand in that realm and then all of a sudden this context that there was no formula for what exactly a website interface should look like. There was not clear boundaries that a website needed to be contained exclusively on screen, those definitions of what the internet would become were still being invented. Though I had no idea what I was doing, I got to witness people who did know more what they were doing, learn from them, and then also I played a role in some of that offering that eventually lead to what we now call UI or UX in the onscreen context.

Then, we were also doing robotics that took in live data feeds from the local airport and that manifested in birds that would flap their wings in duration driven by that data. It was nontraditional self offered work from the studio and then some client based stuff that actually helped lead what would become traditional web design now. It was really fortunate and incredibly educational.

I think getting to see, I don't think they were called this at the time but creative technologists or people who are working directly with the tools or making the the tools that are going to produce the content, and working with people who are engineers and took too a design process from that perspective. This idea that you go in not knowing what it will be and if it will work and that's the bigger question was such a bigger approach than coming from graphic design. Which, at the time had pretty tried and true methodologies and you were using tools that where there were proper ways to use them. Of course I was exposed to exploratory making but the idea that it was okay to say "I don't know, but I will figure it out." Then, eventually build the confidence to say that in a way that I knew I could follow through with. I think that's exactly what that entire community taught me. I'm in debt to that specific experience of working with creative technologists and engineers at Future Farmers.

There's a couple of subsets, essentially. I think would be more traditionally referred to within graphic design practices as thinking through making or just putting aside time to make with no preset objective. The specific R&B that would be going on within the Rockwell Group LAB is a little bit more applicable to a subset of thinking through making that you called making through breaking, which is a little more form focused and it is looking for opportunities in my tools.

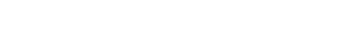

Often times I'll look at a material and do exploratory form studies with materiality and keep documentation of these little form making studies and essentially build up this library of these smaller seeds of ideas that don't have an application. I wasn't making with a goal in mind or a guiding design brief in mind, it was purely figuring out the range of form I can extract from a material. Building up this library of assets, that then later on when I have an insane deadline where I don't have enough time and cushion to do an exploration that doesn't pay off in the end, I can go back to that library of visuals and look for the thing that has an appropriate aesthetic that folds into the meaning behind the design brief. Then pick up what was successful study and make it work in a more applied situation.

So I do that with materiality and tool sets and I approach the whole ... I call it making through breaking not because I'm always intentionally breaking something but just as a reminder that I should do these things in ways that wouldn't occur to me normally and often times aren't ways the tool or material was intended to be used.

I would get a commission now and again from the New York Times but not as consistently when I had moved to rural Alaska. It had actually done a little bit of an intentional shift on my part because going from being a experiential director leading really big teams and then I relocated from being in New York City where I was on site and I could pop in and lead big teams, to moving to rural Alaska where I was definitely not on sight, it made it a little bit more difficult. I knew I needed an alternative means of staying connected. I wanted to have an active relationship with the creative and design community that I'd been affiliated with more in person, but I wanted to be off base having that.

I intentionally started doing some lettering exercises because that is something that you can execute on your own in an isolated studio and that did start pulling in those resources, the visual archives from making through breaking exploration. Initially, I started creating solutions that were self authored. Then I did not reach out or prompt anyone for a commission, but they just started happening. I can't totally explain that, but I was intentionally doing work. I was posting things to Instagram, I was sharing in a public way which is an invitation to be asked to view those things more often.

The invites, the painful sprints, from the New York Times started coming. Alexandra Zsigmond was the person, she's an art director at the New York Times, who invited me to do one of the spot illustrations that became a short series that I think actually got the ball rolling. To her credit, she was the initiator of what became this consistent run of these sprints. Within that framework of the very quick newspaper publishing timeline, I get an invitation, they'd send me the article, I was to read it and usually the turnarounds were, at the longest, a week and a half. At the shortest, sometimes five days or four days, sometimes even shorter, kind of crazy.

That working process of actually writing and doing form making gave me a twofold design thinking process. I was now thinking about copyrighting in one moment and then the next moment I was trying to fold that into enhanced meaning through visuals. My timeline became almost doubled because I was copyrighting and on form making. I would usually give myself a day and a half to copyright, a day and a half to scan my archives for nuggets of goodness that could move me forward in that form making process, and then marry those two together and reconcile what I was missing verbally with something formally. Then I'd send sketches, that's at about three days, to an art director and they would get back to me and I would have two days or three days left to make a final.

All of the process was new, really, and I think that's what made it so painful. It's a very different working mode, which I'm assuming is a model that illustrators ... somebody who had studied illustration for a long time would be much more familiar and comfortable with, it is just running a race for me.

There was no way I could let myself go to sleep because if they said yes to something, it was getting published in a very prominent platform, it would be on the New York Times the next day or within the next couple of days. It pushed me to sequentially not leap and really nitpick the detailing there. It had to be conceptually sound, it had to be visually striking. My name was going on it, which wasn't always the case with the work I was doing before, so I had this other set of prerequisites that I was trying to meet as far as my own tonality in my work and overall voice. I had a lot of expectations for these very short turnarounds.

I gave myself a rule that if I had the time available and sometimes even if I didn't, I had to say yes. Often the only thing that would make me say no was fear that I wouldn't be able to make it happen. I had to say yes and I just had to do it again, and again, and again. That absolutely made me grow, that practice. It became exercises that became very public performative growth exercises. .

The idea of gestural psychology and what I found so appealing about it was that be it reliable or not, it gave me some way of measuring what other people would understand. I think that is rooted in some of my frustration with verbal communication overall. I think there's a kind of beauty in the fallibility in communication and perception and interpretation but also overwhelmingly frustrating. A lot of my self-authored work that is based around language has to do with that, celebrating this miscommunication and this attempt at controlling it and the beauty and the utility in that.

In the framing of visual communication there is meaning embedded in every gesture, be it explicitly written out in language or not being formal, arbitral, etc. I think I'm talking about that, sharing the conversation just as designers this idea of influence through formation and pacing of messaging and all these distinct gestures that we integrate into narrative. Also, there's a moment that you can leave the conversation as an open one and ask for either direct contribution from your audience, a lot of times that would be called conditional design or participatory design, or sometimes you can just leave things as a platform that imply a narrative. Something that would be intended to be used by someone else. In that way, you're literally offering up the starting point of a conversation.

An example of this is, I did an instillation called The Anonymous Hugging Wall which is this weird modelific Snuggie of sorts. It's a giant dividing gesture that's a wall made out of sleeves that's about eight feet tall, so taller than a person, and as long as it needs to be to make it a physical divide so it obscures one side from the other. I put these two lonely little mitten arms jetting out of the center of the wall. I'll install that and just leave that in public spaces. Obviously that's an invitation there, the affordance of the mittens hanging in the middle of the wall is that someone can reach up and insert their arms into this wall. There's no direction and really what that specific conversation that someone enters into is, is totally up to them. That's a big thing that I mean by sharing the conversation, leaving it open for a new narrative to be written into it.

That's the exact reason that I do it. I think that's actually rooted in my fascination with the utility in communication is the variation on perspective and what is going on in someone else's head. A lot of the participatory installs that I do leave room for conversations between multiple people and so it's asking a lot of different people to enter into those vulnerable spaces where there isn't a clear definition of what they should be thinking or how they should be performing. Behaviors and collaborative gestures naturally evolve from that and that type of emergent behavior in spaces is partly contingent on the structure but really the most exciting thing is that it's determined by the participant, the person who's actually choosing to act.

My favorite thing is when somebody walks into one of the spaces that I've installed and does something that I could not have anticipated in any way. It teaches me something, it's surprising. Even when it's a little bit bratty, I'm really excited by the variation of the way people think.

I think I'm dealing with, in a different way, the same thing I was considering when I was talking about that and I'm still moving forward with it. This idea of incorporating an explicit manifestation of lineage in our creative process and a lot of times that comes through the tools we make and who we pass them to and how open they are. I think these tools can come in the form of a piece that is partnered with another piece that becomes a new things when someone else combines them in a different way. So, code combined generatively to output something into physical form, maybe that physical form is actually a mark making tool that somebody else goes on to use. That's an example of this kind of lineage of creative authorship in a whole bunch of different forms that actually incorporate the machine made and the human made into one ongoing process.

I think those are all ways that different people and things can offer what I'm super interested in, which is learning, which I get new opportunities for me to get to lean something new but also new opportunities for me to learn how other people or tools actually approach creation or go about making something. I kind of learn twofold, through the output and through the tool itself. That sounds really nebulous and weird but I'm working on a curriculum right now to be in a very applied space lead other people to create these tools. I think right now it's all come through my mode of thinking, so it has a bias in the voice of where it could go. The first thing that I want to do is diversify who are creating these inaugural tool sets and then basically start a chain reaction and see what this idea of distance collaboration means. I might take those tools from RISD to a different workshop and back to my studio in Alaska and set them on auto play with a milling machine and see what happens.